The AHA! Moment: My Personal Story

The Aha Moment: definition

The moment or instant at which the solution to a problem or other significant realization becomes clear.

Also The Aha! Moment

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/aha_moment

My Definition:

The AHA! moment is when your disparate ideas suddenly rearrange themselves together into a new and insightful pattern.

An enigmatic Rembrandt etching, showing, perhaps,

a thinker receiving a sudden insight.

It's something that every artist, writer, scientist, thinker hopes will happen sooner or later. It usually comes after an extended period of work in an effort to solve a difficult problem. Frustrated, a person gives up and focuses their mind elsewhere. Then suddenly something triggers an insight and the various disconnected pieces of the puzzle now come together to form one coherent picture.

After seven years of writing this blog about the human experience of time, I had one of these moments while driving through drenching thunderstorms as I was fleeing a monster hurricane.

SO HERE IS MY STORY:

I had just finished writing several historical eBooks for a client at Upwork.com about the Industrial Revolution, the Scientific Revolution, the Neolithic Revolution, Greek Mythology and Galileo. Each 10,000 word eBook was long enough to go into some detail but short enough that I would not get bogged down in endless minutia. It was the perfect assignment for me -- because I like to look for the big overview, the big picture, while also finding substantial facts and historical events to back up my conclusions. And after writing these eBooks I was musing about the many theories and discoveries that had become part of civilization today.

Then I started to think about my own ideas concerning the human experience of time -- the purpose of this blog, DeconstructingTime. I have been working on this subject for seven years. I was confident that I had mapped out a pretty good set of ideas and yet at the same time, I felt there was something missing. I wanted a larger hypothesis that could tie many, if not most, of my ideas together.

Around this time I also had begun to entertain a new point of view about the human condition. Rather than thinking of us as civilized people who occasionally succumbed to animal behavior, I began to think of us as basically animals who were doing their best to be civilized. And this switch in perspective opened up an entirely new way of looking at things.

Fresh from my eBook research, I thought of Mendeleev who put together the first working chart of the elements that make up all matter, a chart that is now known as the periodic table. He had put each element and what he knew about it, such as its atomic weight, on a card and then laid out these cards as though he was playing a kind of solitaire. He did this for a number of years until one night he had a dream and saw the entire periodic table almost perfectly arranged.

"I saw in a dream a table where all elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper, only in one place

did a correction later seem necessary."

Dmitri Mendeleev

did a correction later seem necessary."

Dmitri Mendeleev

Mendeleev (left) and his notes about the periodic table. His work has become the basis for our understanding of the material world and is considered a milestone in scientific thought.

One of my own personal quests has been to go back as far as possible in history to find the moment when we Homo sapiens began to think about time in terms of past, present, and future and then, as a result, were able to make plans. I assumed that before that, like virtually all animals, Homo sapiens were locked into the present, into the here and now, and that they lived entirely in the moment. So before this, we/they could not plan.

I also knew that after perhaps hundreds of thousands of years when we/they had emerged from their instinctual animal existence, they did develop modern languages with a full set of expressions, concepts, and metaphors to describe and work with time in a linear fashion, i.e., past, present, and future. And this allowed planning, coordinating and sharing, i.e., all the things that made Homo sapiens so powerful and dominant on the planet. In other words, language gave us the tools to work with time.

But the period in between our original animal existence and a fully developed language was a dark mystery. I could not imagine an early language nor could I imagine an initial or early developing sense of time.

Then as chance would have it, a huge hurricane, Hurricane Florence, threatened the home where I lived, and I had to leave in the middle of the night after getting an ominous phone message from the government. There was a mandatory evacuation order for my area of North Carolina.

Once I had loaded the car, locked up the house, and was on the road at 2 AM, I began to think about my work on the subject of time. Alone in my car with virtually no traffic, it was kind of dreamy but foreboding as well. To give myself something to think about I decided to talk to myself and see if I could make some headway.

I have always been interested in the passage of time, starting perhaps with T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets which give the best definition of time that I know of. As I have quoted many times before in this blog, Eliot points out that time is always now -- and without the now moment time would not happen.

At the still point of the turning world.

Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards;

At the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement.

And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered.

Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline.

Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance,

And there is only the dance.

...

And all is always now

T.S. Eliot, Burnt Norton, 1936, Four Quartets

In the 1980s I had studied the time lapse photos of Eadweard Muybridge for two years and then made computer art based on his study of human locomotion. And as a photographer for fifty years, I understood time and timing because photography concerns itself with both. More recently I created an extensive study of what I call time-flow photography, photography in which I took pictures with long shutter speeds to show blur, motion, and the passage of time.

A reworked digital image from Muybridge's

Woman in Motion photography series.

A candid photograph created entirely with slow shutter speed

'time-flow' effects and not with software.

I had also made the connection between language and our concepts of time. I had written a blog about a year ago on that subject. In the process of writing, it became clear to me that language was in many ways the key, as it gave us humans the tools to conceive of time in complicated ways and also to express those concepts to others. But that was as far as I got.

How Our Concept of Time Is Embedded & Derived from Our Language

For words are to thought what tools are to work;

the product depends largely on the growth of the tools.

Will Durant, History of Civilization: Part 1

Then in the occasional bursts of heavy rain that made it almost impossible to see the road with my headlights, even though the wipers were going full speed, the first clue came to me.

A hurricane track over the coast

in North Carolina where I live.

I remembered reading that there was a tribe in the Amazon that spoke a very different language -- some called it a more basic language -- which no linguist or researcher had come across before. It did not follow any of the normally accepted rules that virtually all other languages followed.

Around dawn after five hours on the dark road, I reached my destination, the home of a long time friend, Harry. Harry lived in Durham and had graciously allowed me and my wife, who was already there, to stay with him.

AFTER THE STORM

So my lonely night journey to escape the storm brought together a number of ideas.

I announced to Harry the following morning that I was going to use this time, while we waited out the storm, to find out about this tribe. A quick search of the Internet told me that the tribe was called the Piraha and that Daniel Everett, a kind of revolutionary linguist, was the accepted expert of their culture and language.

After watching everything I could on YouTube, listening to Dan Everett's TED talks, and reading numerous articles by Everett and others on the Internet, there it was: The Missing Piece.

When I had read about the tribe years earlier, Everett had not formulated a comprehensive hypothesis of language. But now he had and to my incredible surprise, it was a perfect fit with my own ideas. It turned out that about six months earlier -- but about a year after I had written my own post about the connection between time and language -- Everett had written a book entitled, How Language Began.

Without realizing it, I had laid out cards in my mind, as Mendeleev had done, yet there was this big blank card in the middle. But now the Piraha and the ideas of Dan Everett had filled this gap.

Time reference is a universal property of language...

Jacqueline Lecarme, PH. D., Linguistics

The following is what I grasped from Everett's ideas:

Language is much much older than previously thought and goes back to the predecessors of us humans (Homo sapiens); it goes back to Homo erectus more than a million years earlier. Everett decided that altogether there were probably three language stages: G1, G2, and G3. The languages today are all G3 except that of the Piraha which is an earlier language, a G2 language. Everett suspects there are many more in the world, they just have not been understood properly.

We use language in a sophisticated manner without realizing that it has given us

the symbols to work with time in complex ways.

Language, however, began with the earliest language, G1, which was spoken by Homo erectus a million years ago, and which gradually developed due to the cultural and survival needs of these people.

I always felt that the human sense of time must have developed slowly (meaning a million or so years) but there was no evidence to support that. And so it seemed unlikely that we would ever discover an early language since it was probably spoken by prehistoric people who had left no record. In addition, it was generally assumed that language began with us, Homo sapiens, and that it might not have developed until relatively recently, such as one hundred thousand years ago. Everett's timetable, however, pushed the start of language back much further.

NOTE: While I believe language may have taken a million or so years to develop, this time table is not crucial for my hypothesis. A shorter timetable could definitely be possible. What's important is the sequence and nature of the development of language and the concepts of time as I have outlined them here.

So with Dan's hypothesis and the clear evidence of the Piraha's basic language, it now seemed to me that the history of language was quite different. A living language of the contemporary tribe, the Piraha, with a very old tradition of hunting-and-gathering showed what an earlier language could sound like.

THE AHA MOMENT

The AHA moment came when I realized that not only had Dan Everett found an earlier language but the language and culture were entirely based in the moment and in the here and now -- in the Immediacy Of Experience Principle, as Dan called it.

This language and culture had a very different sense of time and that understanding of time was anchored in the present -- a sense of time that was much closer to instinctual animal behavior. Since my work has been about the human experience of time and how the concept and experience of time have changed as lifestyles and technology changed, the Piraha sense of time was exactly what I had predicted if an earlier language could be found. This was especially true for people living a day-to-day hunter-gatherer existence as early humans must have done.

And also if that was true, then a hypothetical earliest G1 language would also be based in the here and now with an even greater sense of immediacy. Until I learned about the Piraha, I could not imagine an early language. But now because of their language, it was possible to project back to the beginning and sketch out how the first stages would be put together and also what their sense of time would be like.

------------------------- EUREKA! -------------------------

QUICK SUMMARY OF MY AHA! UNDERSTANDING: As we know, all languages reference time but the earliest languages probably had a very different concept of time than we have today. These early languages had a here-and-now immediate sense of time that then took hundreds of thousands of years to develop into the modern linear sense of time.

It turned out that the Piraha language provided the crucial intermediate point in between our early animal behavior and today's fully developed modern languages.

So here is how my ideas fit so nicely with those of Everett.

This is a recreation of Australopithecus who is considered our distant ancestor

and who almost certainly had not developed language at this point.

Since we were animals first and humans later, there must have been a time when we humans lived like the animals, i.e., entirely in the present. In other words, past and future did not exist along with planning and coordinating. So the human sense of time must have evolved gradually from an animal state and done so in coordination with the gradual development of language. This was because language was the primary tool that could conceptualize time and then allow the sharing of plans and the manipulation of time.

It was clear from the stone tool evidence left by Homo erectus that they understood processes which required a sense of time and that this knowledge was passed down from generation to generation.

These sophisticated stone tools have been accurately dated back to 300,000 BCE.

They were made by the earliest Homo sapiens. Homo erectus tools are much older.

An early sense of human time would be part animal that lived in the present and part human that conceived of time in a limited way and that coincided with Everett's language stages. And now I could make an educated guess about the concepts of time in each language stage. Early time concepts would be very different from the sense of time we experience today.

In other words, early members of the genus Homo invented our concepts of time and then during the long development of these ideas, there were markedly different concepts of time. These depended on the needs of the culture, the environment, the technology, and the changing weather. The sense of time we have today in the industrial world is quite different from the sense of time in the Neolithic/agricultural era which in turn was quite different from the sense of time when people lived in tribes and were nomadic and/or hunters and gatherers in the forest or the jungle.

These are members of the hunter-gatherer Piraha tribe in the Amazon today who live by the Immediacy Of Experience Principle according to Daniel Everett.

This means their concept of time is anchored in the near-present

and quite different from the modern world.

Everett also believes they speak a G2 language

which might be an earlier form of spoken language.

Everett also believes they speak a G2 language

which might be an earlier form of spoken language.

And with that my hypothesis of the human-sense-of-time now had a pedigree, meaning that human ideas about time had a clear beginning and that they then continued to develop right up to today. And it was completely intertwined with the development of language because language provided the tools for working with time.

About a month after this, I formulated "A Comprehensive Hypothesis About the Evolution of Language and the Human-Sense-Of-Time." In this paper, I outlined a basic sequence for the development of language and the development of time concepts. The AHA! moment had now turned into a full-blown hypothesis. Voila!

A Comprehensive Hypothesis About the

Evolution of Language and the Human-Sense-Of-Time

After this theory about language, I went one step further and expanded these ideas to include culture, technology, and belief systems.

An Expanded Hypothesis That Relates the History of the Human-Experience-Of-Time

to Culture, Technology and Belief Systems in Addition to Language

The many languages of the world.

AFTERWORD

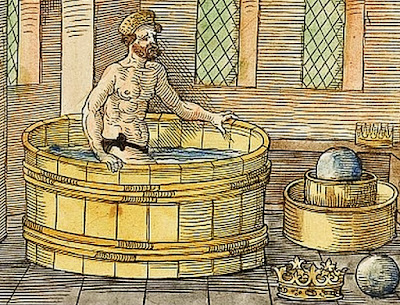

Archimedes in his bath, just before his Eureka moment.

The most famous Eureka story occurred when Archimedes of Syracuse around 250 BCE was trying to discover a way to determine whether an intricate gold crown was really solid gold as the King of Syracuse, Hieron, had ordered from a metalsmith. The king suspected that it was partly silver which was hidden behind the gold and so ordered Archimedes to determine its true composition. According to legend, Archimedes had been struggling with the problem for some time and finally gave up and took a bath. When he got into the full bath, he realized that water now overflowed due to the density of his body. Then in a flash, he understood that placing an object in water would displace the water and that the volume of displaced water would allow him to make a calculation about the density of the metal -- since silver and gold had different densities. And that was the Eureka moment. Eureka means, "I have found it" and according to legend Archimedes forgot that he was naked, jumped from his bath and ran through the streets shouting, "Eureka! Eureka!" And, BTW, it turned out that the crown was not entirely gold, so the king was justified in his suspicion.

Galileo had an AHA! moment when he saw a lamp swinging from a long cord while he was at a church service. He then measured the time of its swings with his pulse. His work led to the first formulas that included a complex understanding of time.

After frustrating months of work, Einstein either got in a trolley or imagined that he did, as he had ridden it many times. In any case, the ringing of the bell by the ancient clock (behind the trolley) in Bern Switzerland triggered a vision in which the trolley was suddenly moving at the speed of light. Einstein then realized that the time showing on the Bern clock-face could never catch up with the trolley. And this became the basis for his Special Theory of Relativity.

MORE ABOUT MENDELEEV & THE PERIODIC TABLE

The Mendeleev insight is particularly interesting because it was not entirely correct but was close enough that it eventually led to both a precise understanding of the nature of each element and also how these elements came to exist. So the periodic table became a basic road map of all matter that makes up everything that exists.

If all the elements are arranged in the order of their atomic weights, a periodic repetition of properties is obtained. This is expressed by the law of periodicity.

— Dmitry Ivanovich Mendeleev

NOTE: Mendeleev was close but not quite right. It turned out that elements needed to be arranged in order of their atomic number (the number of protons) and not their weights. But the atomic number was not well understood until almost 45 years later.

For the first time I saw a medley of haphazard facts fall into line and order.

C.P. Snow

The eighth element, starting from a given one, is a kind of repetition of the first, like the eighth note of an octave in music.

— John Alexander Newlands

Mendeleev's insight led eventually to theories about how each element was created. It turns out they were mostly created (cooked as Neil DeGrasse Tyson says next) in the centers of stars and the explosions of stars. So Mendeleev's concept reached far into the nature of mater itself.

One of the great triumphs of 20th Century astrophysics, was tracing the elements of your body, of all the elements around us, to the actions of stars—that crucible in the centers of stars that cooked basic elements into heavier elements, light elements into heavy elements. (I say “cooked”—I mean thermonuclear fusion.) The heat brings them together, gets you bigger atoms, that then do other interesting chemical things, fleshing out the contents of the Periodic Table.

Neil DeGrasse Tyson

MORE ABOUT THE IDEAS IN THIS BLOG

For people who are not familiar with this blog over the last seven years, here are some of my most important blog-posts:

== In my most popular blog-article I wrote that humans have a unique sense of time, an enhanced sense such as dogs have with smell, due to the prefrontal cortex in the brain. Dan Everett seemed to agree with this idea in his book How Language Began published more than three years after my blog article. This blog-article is my most important one and has been viewed and downloaded over 7000 times.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2014/08/animal-senses-compared-to-human-sense.html

== Another blog-article made the point that all languages include ways of expressing time and conceptualizing time. This blog-article would become a key part of my thinking.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2017/02/concept-of-time-embedded-in-language.html

== I have also shown that Neolithic people had a precise pre-scientific method for measuring the yearly seasonal cycles which was key to their sense of time.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2015/03/computing-winter-solstice-at-newgrange.html

And while I was pleased with these different pieces of research, I was looking for an overall hypothesis that would tie many of these ideas together.