The Tribal-Wide Use of Processes

in the Paleolithic Era

Free Download

A PDF of this blog-article at:

https://unc.academia.edu/RickDoble/DRAFTS#drafts

ALSO FREE:

The Illustrated Theory

of Paleo Basket-Weaving Technology

by Rick Doble

Download a 200-Page PDF eBook

-- no ads/no strings --

DOWNLOAD NOW

Figshare

Academia.edu

Free Download

A PDF of this blog-article at:

https://unc.academia.edu/RickDoble/DRAFTS#drafts

ALSO FREE:

The Illustrated Theory

of Paleo Basket-Weaving Technology

by Rick Doble

Download a 200-Page PDF eBook

-- no ads/no strings --

DOWNLOAD NOW

Figshare

Academia.edu

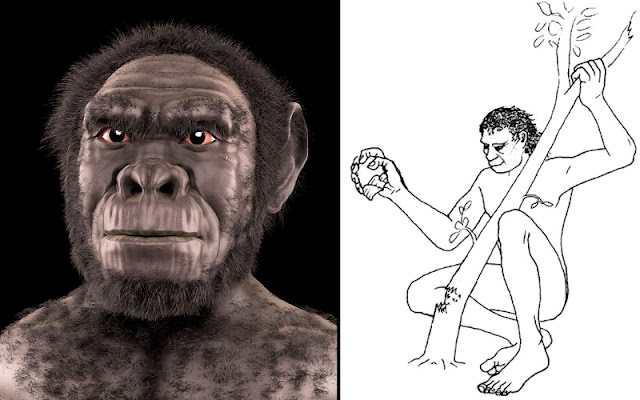

In my last four blogs (see links at the bottom) I made the argument that Paleolithic *processes* were at the heart of human evolution. They began with the stone-tool technology of Homo habilis and have continued up to today.

I have further argued that these processes evolved and became more complicated as the brain of hominins grew larger. And with the help of their brain's unique large prefrontal cortex, hominins began to understand the workings of linear time -- time with a past, present, and future -- since processes proceed step-by-step in linear time.

MY NEW POINT

All of the above implies one major additional point. If the above statements are true, then the entire tribe of people would have probably been familiar with processes: from men (presumably) making stone tools to women (traditionally) harvesting and preparing food to children learning and helping in the making of processes.

An example of other processes:

-- While paleoanthropologists have assumed that men were making stone tools, they have also assumed that there was probably a division of labor. Women, in general, were in charge of finding food and preparing food. And this was a process all its own. Assuming that women's skills were as advanced as stone-tool making, they would have evolved their own food gathering and preparation processes.

-- In nomadic tribes women would probably have known which plants were best for eating at a certain time of year in each of the different nomadic environments. They would also have known the location, the right time to harvest, how to harvest (with special tools perhaps), how to carry the harvest and then how to prepare the plants for a meal (also with special tools perhaps). These food-related processes may have been as sophisticated as the stone tool technology at the time.

In addition, children probably helped and were taught about these processes from an early age.

"In a hunter-gatherer society, the hunters were usually men and the gatherers women (according to the latest research) -- although these roles were a bit flexible. This model, however, does not assume that men were dominant as a recent study has shown."

Devlin, Hannah. "Early men and women were equal, say scientists." The Guardian US, New York, NY, May 14, 2015.https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/may/14/early-men-women-equal-scientists

Just like the men knowing where to look for stones for stone tools, the women would know where to look for promising vegetation. Like the men knowing which stones to break open, the women would know which plants and parts of plants (such as seeds, nuts, and roots) to use for food along with gathering larvae, eggs, and honey. And like the men breaking the core stones apart the women would know how to harvest. And also like the men knowing which tool was best for skinning an animal or cutting down a small tree, the women would know how to prepare the food for eating.

Later when hominins began to use fire, she would also have needed to know how to find wood, work with coals, and keep a fire going even if the wood was green or wet. This was probably a shared responsibility with her mate, but it was a skill that she needed to master as well. And fire added another level to a woman's food processes -- with cooking, baking, curing, etc. In many societies, women had a special relationship with fire that was revered by the community.

The expression, "Keep the home fires burning," still used today, refers to a woman maintaining a warm fire in the fireplace when her husband is away and what he will find when he returns. Also the expression 'home and hearth' implies the same relationship.

While we cannot know what occurred in the Paleolithic era, it is clear that women had a special relationship to fire in many ancient societies. In Rome, for example, the Vestal Virgins kept an eternal flame alive. The Romans believed that keeping the fire going protected Rome. This ritual was at the center of Roman culture and it lasted for more than 1000 years until just before the fall of Rome (700 BCE - 391 CE). The ritual was in honor of the Goddess Vesta, an ancient Roman Goddess of hearth, home, and family. She was rarely depicted in human form but instead as a flame or fire itself, recalling what many anthropologists believe were the most ancient animistic beliefs of the earliest human cultures.If women had their own processes in addition to the male processes of stone-tool making, this means that the idea of processes was tribal-wide. So the experience of working with processes, i.e., processes as a metaphor and processes as a model for the progression of linear time was something that was understood by everyone in the tribe. There also had to be a method for teaching about processes so that this information could be passed down from generation to generation.

And because this understanding was tribal-wide, the experience of working with processes was something that everyone could share, refer to and communicate about. So since men, women, and children all worked with processes, they could communicate with each other using various processes as a point of reference.

This is an important point because the later leap, so to speak, into behavioral modernity required that everyone in the tribe understood the developing language and the emerging culture. Working with processes would have provided that common experience and ways of communicating which then led in part to a fully developed language.

As I have written earlier, working with processes would also have led to an understanding of linear time, since all processes involve linear time (past-present-future and duration) in their step-by-step procedures. And this understanding of time was critical for the development of a full language, the development of culture and for achieving modern human behavior.

It is also possible that various rituals were based on the idea of processes. When a person died, for example, a certain ritual, which had to be performed in a specific order, was required. Such a ritual conformed in many ways to the step-by-step sequences in a process. But in this case, the desired outcome of the process was to influence spiritual or supernatural elements.

AFTERWORD

The Consequences Of Developing Processes

Working with and using processes had many ramifications besides an understanding of time and a possible language associated with it.

Working with processes meant that hominins were discovering different qualities in different materials. Some rocks broke apart to make a tool with sharp edges, for example, but most did not. As a result, hominins may have felt that each material had its own nature or as we would say its own properties.

Working with processes also meant that humankind was now beginning to make the environment adapt to its needs rather than humans adapting to the environment, like most of nature.

"The Oldowan [ED: i.e., the first stone tools] represents the first instances of technological innovation in human history, wherein our ancestors first began to enhance their biological abilities with the manufacture of stone tools."

Turcotte, Cassandra M. "Oldowan Stone Tools." The Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology (CASHP).

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/origins/oldowan_stone_tools.php

Eventually, this may have led to a sense that people were different from the other animals and separate from nature which in turn led to a sense of separateness and superiority. This was both empowering and frightening. The basic sense of connectedness to nature had been altered and humans would have to find a way to mend that gap.

This then may have led to an animistic sensibility which the study "Hunter-Gatherers and the Origins of Religion" (reference below) said could have existed even before a fully developed language. Everything in nature had different properties and it was the task of hominins to understand or discover what those properties were.

Each person and each element in nature was seen to be alive with a unique spirit of its own. So this may have given rise to an animistic sensibility which is now seen as the most basic spiritual state (see reference next) although it is not a religion. This eventually, however, may have led to the beginnings of religion. In this view, animals, trees and rivers would have been seen as having a spirit, just like human beings but each with its own nature. And it was the job of humans to understand this nature and to work with it.

"Results [of our study] indicate that the oldest trait of religion, present in the most recent common ancestor of present-day hunter-gatherers, was animism... [Next a] belief in an afterlife emerged..."

Peoples HC, Marlowe FW, Duda P. "Hunter-Gatherers and the Origins of Religion."

Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Published online: 6 May 2016 open access at Springerlink.com.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12110-016-9260-0

Eventually, the loss of connectedness may have led to the beginnings of religion, which was, in part, an attempt to bridge that gap: to find an explanation about why humans were different from the rest of the animal kingdom and to console people about the inevitability of death.

Speaking about the much later Paleolithic temple, Gobekli Tepe, Charles Mann "suggests that the human impulse to gather for sacred rituals arose as humans shifted from seeing themselves as part of the natural world to seeking mastery over it."

Mann, Charles. "The Birth of Religion." National Geographic Magazine, June 2011, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2011/06/gobeki-tepe/

About Animism

"Our results reflect Tylor’s(1871) belief that animism was the earliest and most basic trait of religion because it enables humans to think in terms of supernatural beings or spirits. Animism is not a religion or philosophy, but a feature of human mentality, a byproduct of cognitive processes..."

Peoples HC, Marlowe FW, Duda P. "Hunter-Gatherers and the Origins of Religion."

Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Published online: 6 May 2016 open access at Springerlink.com.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12110-016-9260-0

About Reconstructing The Past

"Giambattista Vico [ED: a history philosopher] believed that every theory must start from the point where the subject of which it treats began to take shape."

Whitrow, Gerald James. Time in History: Views of Time from Prehistory to the Present Day. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press. 1988, page 150.