Basket-Weaving in the Paleolithic Era

ABSTRACT:

More than 100 years ago Gustave Chauvet wrote that he believed basketry and simple weaving were present in the Upper Paleolithic sites he had studied. Yet it took almost that long to convince experts that this was the case. The discovery of irrefutable evidence in the form of impressions of weaving in clay provided the proof. Now it is clear that basket-weaving and textile-weaving were not incompatible with the hunter-gatherer Paleolithic lifestyle and did not require the sedentary settled Neolithic way of life as had been assumed. This opens up the idea that basket-weaving or woven-fiber technology as I have called it, could have begun even in the Lower Paleolithic, millions of years ago. What follows in the rest of this article is a summary of my seven articles over the past year in which I outline how basketry could have begun perhaps two million years ago and then how it could have developed until the rise of the great civilizations of Sumer and Egypt which depended on this technology. I conclude with ideas about how to find indirect evidence of basket-weaving in the Paleolithic era.

See a listing of 14 blogs about basket weaving technology from its earliest stages in the Paleolithic era to its implementation in the world's first civilizations.

Free Download

A PDF of this blog-article at:

https://unc.academia.edu/RickDoble/DRAFTS#drafts

ALSO FREE:

The Illustrated Theory

of Paleo Basket-Weaving Technology

by Rick Doble

Download a 200-Page PDF eBook

-- no ads/no strings --

DOWNLOAD NOW

Figshare

Academia.edu

among the first of the arts given to humans."

The tools are a knife, awl, curved awl, and rapping iron.

It is from the basket making website of Willow Basketmaker (https://www.willowbasketmaker.com) reprinted by permission.

A small number of tools are all that is required to make baskets and woven objects. All of these tools or similar tools could have been made by Paleolithic people, as their basic design is not difficult. So it is possible that many of the unidentified tools that have been found in Paleolithic caves could have been basket-making tools.

"In whichever way archaeological remains are interpreted, one must always be aware that the vast majority of the materials with which prehistoric people were surrounded and with which they worked is lost to us today. ...organic materials start to decay as soon as they are deposited in the ground." [12]

"This lack of archaeological visibility contrasts with the importance attributed to these perishable materials and techniques in some ethnoarchaeological studies, which highlight the extremely high proportion of objects made with them and the techniques compared to those made from stone and bone."[13]

Please Note: The following footnotes 16-19, 21, 23 link to and refer to my detailed articles about different aspects of prehistoric basket-weaving.

As Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth pointed out, "It is likely that this phenomenon of accelerated brain expansion in the human lineage was due to the ability of hominins to access higher quality food resources through the use of technology, which allowed for a decreased gut size and increased brain size."[20]

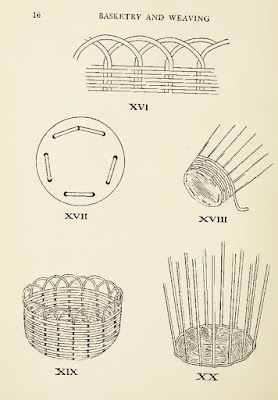

showing the right angle construction of basket-weaving.[22]

From Prehistoric Textile Fabrics Of The United States, Derived From Impressions On Pottery

by William Henry Holmes, published in 1884.[27]

Writing about the very early Oldowan tools of a million or so years ago and their use on the African savanna, Dr. Toth of the Stoneage Institute said, "As plant processing in Oldowan times is a nearly invisible activity due to the general lack of preservation of macroscopic plant remains, this microwear evidence provides an invaluable window into this aspect of early hominin adaptation. The plant-cutting knives show classic ‘sickle gloss,’ indicating the gathering or processing of soft plants, whether for food, bedding, or other purposes." And African savanna grasses were also ideal for basket-weaving. [26]

and 6 cm (about 2.5 inches) wide at the top.

Speaking about the lack of archaeological interest in basketry, mats and textiles, Grace M. Crowfoot wrote the following in A History of Technology, Volume 1. "In considering gaps in the knowledge of textiles, it must be remembered that there are vast areas where little archaeological study has been undertaken...Surviving pieces of rag were often rejected as without interest...Determination of the exact botanical origin of the fibres used in basketry and weaving has only quite recently been recognized as of archaeological importance."[36]

NOTE:I use Native American culture and basketry as an example because many tribes were particularly skilled in basket making and many anthropologists believe that their hunter-gatherer lifestyle was similar to that of the Upper Paleolithic in Europe.[37]

Art Craft Institute, Chicago, 1902, p.6.

Baskets were used for utilitarian and ceremonial purposes. They were well suited to a seasonal subsistence lifestyle once practiced by many Indian tribes because they were light and durable. Various basketry forms were used in the gathering, processing, and cooking of food resources. Important events such as rituals, weddings, and other rites of passage were celebrated with gifts of beautiful baskets decorated with feathers, beads, wool and shell pendants. In all of their forms, these baskets demonstrated the great artistic skill and attention to detail that went beyond their actual usefulness.Whether coiled, twined, or plaited, baskets were woven from a variety of native plant materials, with little more than an awl and knife. Weavers and their families tended and harvested numerous plants on a yearly basis throughout basket-making communities.The preparation of weaving materials often took as long as the actual weaving process itself.

__________________________________________________________________

FOOTNOTES

NOTE:

Many of my sources and ideas were inspired by the following excellent work:

Wigforss, Eva. "Perished Material - Vanished People Understanding variation in Upper Palaeolithic/Mesolithic Textile Technologies." Master Essay, Lund University, 2014.

[1] Bahn, Dr. Paul. (2001). "Palaeolithic weaving – a contribution from Chauvet." Antiquity, 75:271-272.

[2] Dawkins, William Boyd. Early Man In Britain And His Place In The Tertiary Period. Macmillan, London, 1880, p. 185.

https://archive.org/details/earlymaninbritai00dawkrich/page/n7

[3] Department of Archaeology, Durham University. "Palaeolithic art and archaeology of Creswell Crags, UK." 2020.

https://www.dur.ac.uk/archaeology/research/projects/all/?mode=project&id=639 Accessed 09/23/2020.

[4] Hyland, David C.; Zhushchikhovskaya, I. S.; Medvedev, V. E.: Derevianko, A. P.; Tabarev, A. V. "Pleistocene Textiles in the Russian Far East: Impressions From Some of the World's Oldest Pottery." Antropologie: Xl/1 • Pp. 1–10 • 2002, p. 1.

[5] California Department of Parks and Recreation. "American Indian Basketry." 2020.

https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=24166 Accessed 09/23/2020.

[6] Morse, T. Vernette, Mrs., Basket Making (How To Do It Series). Art Craft Institute, Chicago, 1902, p. 2.

[7] Chauvet, Gustave. 1910. Os, ivoires et bois de renne ouvrés de la Charente. Hypothèses palethnographiques. (Bones, ivories and worked reindeer antlers from the Charente.) Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société archéologique et historique de la Charente (8° série) I: 1–184.

[8] Soffer, Dr. Olga; Adovasio, Dr. James. "Perishable Industries from Dolní Vestonice I: New Insights into the Nature and Origin of the Gravettian." Archaeology Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, January 2001. (Available online: DolniVestonice.pdf)

[9] Soffer, Adovasio, 2001.

[10] Menon, Shanti. "The Basket Age." Discovery Magazine, January 1996 Issue. http://discovermagazine.com/1996/jan/thebasketage619

[11] The University of Cambridge. "Farmers have less leisure time than hunter-gatherers." ScienceDaily, 21 May 2019. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/05/190520115646.htm>. Accessed 09/23/2020.

[12] Grömer, Dr. Karina. "An Introduction to Prehistoric Textiles." Brewminate.com, Natural History Museum, Vienna, March 01, 2016,

https://brewminate.com/an-introduction-to-prehistoric-textiles Accessed 09/23/2020.

[13] Aura Tortosa, J., Pérez-Jordà, G., Carrión Marco, Y. et al. "Cordage, basketry and containers at the Pleistocene–Holocene boundary in southwest Europe. Evidence from Coves de Santa Maira (Valencian region, Spain)." Veget Hist Archaeobot 29, 581–594 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-019-00758-x Accessed 09/23/2020.

[14] Soffer, Adovasio, 2001.

[15] Lucas, C., Galway-Witham, J., Stringer, C.B. et al. "Investigating the use of Paleolithic perforated batons: new evidence from Gough’s Cave (Somerset, UK)." Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11, 5231–5255 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-00847-y Accessed 09/23/2020.

[16] Doble, Rick. "Paleolithic Evidence Shows That Homo Habilis Could Have Learned Weaving From Weaverbirds (Ploceidae)." Blogger.com, 2019.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2019/10/paleolithic-evidence-for-early-weaving_27.html

[17] Doble, Rick. "Evidence That Paleolithic Hominins Lived in Close Association With Weaverbirds and Their Basket Making Skills." Blogger.com, 2020.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2020/04/oldowan-weaverbirds-homo-habilis-basket-making.html

[18] Doble, Rick. "The Invention of Right-Angle Construction in the Paleolithic Era." Blogger.com, 2020.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2020/08/invention-of-right-angle-in-paleolithic-era.html

[19] Doble, Rick. "The Importance of Processes in the Paleolithic Era." Blogger.com, 2019.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2019/11/the-importance-of-processes-in.html

[19A] Doble, Rick. "The Tribal-Wide Use of Processes in the Paleolithic Era." Blogger.com, 2019.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2019/12/the-tribal-wide-use-of-processes.html

[20] Schick, Kathy, and Toth, Nicholas. "THE OLDOWAN: Case Studies into the Earliest Stone Age." Stoneage Institute Publication Series, Schick, Kathy and Toth, Nicholas (Eds.). Stone Age Institute and Indiana University, Stone Age Institute Press, 2006, p. 35.

[21] Doble, Rick. "The Invention of Right-Angle Construction in the Paleolithic Era." Blogger.com, 2020.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2020/08/invention-of-right-angle-in-paleolithic-era.html

[22] Pasch, Katherine. Basketry and Weaving in the School. A. Flanagan, Chicago, 1904, p. 16.

[23] Doble, Rick. "Evidence for a Basket Weaving and Woven-Fiber Technology in the Paleolithic Era." Blogger.com, 2019.

https://deconstructingtime.blogspot.com/2019/09/evidence-for-basket-weaving-technology.html

[24] The Tigris expedition: A National Geographic Special (documentary about Thor Heyerdahl's expedition). National Geographic Society, broadcast on PBS 04/01/1979.

[25] Lakeside Pottery. "Clay and Pottery - Brief History." 2020.

http://www.lakesidepottery.com/HTML%20Text/brief%20history%20of%20clay_pottery.htm Accessed 09/23/2020.

[26] Schick, Toth, 2006:35.

[27] Holmes, William Henry. "Prehistoric Textile Fabrics Of The United States, Derived From Impressions On Pottery." Third Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1881-82, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1884, pages 393-425, p. 396.

[28] "Oldowan and Acheulean Stone Tools." Museum of Anthropology, University of Missouri.

https://anthromuseum.missouri.edu/exhibit/oldowan-and-acheulean-stone-tools Accessed 09/23/2020.

[29] Handaxe. Flint. Acheulean industry, Lower Palaeolithic, 800,000 - 300 000 BP. Abbeville, St. Acheul, Somme, France.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Acheulean_implements._Flint._Abbeville,_St_Acheul._Neues_Museum.jpg Accessed 09/23/2020.

[30] Benguigui, Macarena, and Miguel Arenas. “Spatial and temporal simulation of human evolution. Methods, frameworks and applications.” Current genomics vol. 15,4 (2014): 245-55. doi:10.2174/1389202915666140506223639

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4133948/ Accessed 09/23/2020.

[31] Hardy, M. 1891. "The quaternary station of Raymonden in Chancelade (Dordogne) and the burial place of a hunter from Rennes." Bulletin of the Historical and Archaeological Society of Périgord 18, p. 24.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_station_quaternaire_de_Raymonden_(...)Hardy_Michel_bpt6k5567846s_(3).jpg

[32] Picture information: Grotte du Trilobite, Arcy-sur-Cure, Yonne, Burgundy, France. Taken from Abbé Alexandre Parat, Les Grottes de la Cure (côte d'Arcy): La Grotte du Trilobite, plate 3 (between pp. 32-33). Bone tools.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grotte_du_Trilobite_-_Arcy_-_os_ouvr%C3%A9s,_planche_3.jpg

Pictures from the book:

Parat, M. l'abbe A. Les Grottes de la Cure (cote d'Arcy). Auxerre, 1903.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k141509c/f38.item.zoom

[33] Lochstab_Kostenki.jpg "Perforated rod made of Kostjonki, mammoth ivory, approx. 25,000 BP."

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lochstab_Kostenki.jpg

[34] Handwerk, Brian. "A Mysterious 25,000-Year-Old Structure Built of the Bones of 60 Mammoths." Smithsonianmag.com, March 16, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/60-mammoths-house-russia-180974426/

[35] Frazer, Sir James George. The Golden Bough: A study of magic and religion. Macmillan and Co., London, 1890.

http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/3623/pg3623.txt

[36] Charles Singer, E.J. Holmyard, A.R. Hall. A History of Technology, Volume I: From Early Times to Fall of Ancient Empires. Oxford University Press, 1954. (Kindle location = 8905)

[37] Hyland et al, 2002:1.

[38] Boule, Mary Null. "Hupa Tribe." Kahle/Austin Foundation, 1992.

[39] Porter, Barbara Nevling. Trees, Kings, and Politics Studies in Assyrian Iconography. Academic Press Fribourg Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen, 2003, pp. 50-51. Porter_2003_Trees_Kings_and_Politics.pdf