TIME-TRAVELTO A MESOPOTAMIAN CITY5,000 YEARS AGOThis blog-article is Part #2 of my previous blogThought Experiments & ImaginationThis blog-article is an example of how to use your imagination to explore the ancient and prehistoric past. In this article, you imagine what it would be like to walk around a Mesopotamian city 5000 years ago.Hall in an Assyrian Palace. -- from a later time than our following story.Artist's conception "By James Fergusson in the "Nineveh Court" of the Crystal Palace - Reconstruction 1854."

PREFACE

This is the second half of my article about thought experiments and using your imagination in the study of prehistory. But this idea could be applied to any number of tasks. Please read the first article by clicking on this link or scroll down to see it below this one.

In the first article, I detailed thought experiments by Galileo and Einstein along with my own imaginings plus a current example. But the main point of the article is to encourage others to use their own imaginings in their work.

So the following is an example of how you could use your imagination. But, of course, there are many ways to do this.

INTRODUCTION

This blog-article is Part #2 of my previous blog

Thought Experiments & Imagination

This blog-article is an example of how to use your imagination to explore the ancient and prehistoric past. In this article, you imagine what it would be like to walk around a Mesopotamian city 5000 years ago.

Hall in an Assyrian Palace. -- from a later time than our following story.

Artist's conception "By James Fergusson in the "Nineveh Court" of the Crystal Palace - Reconstruction 1854."

PREFACE

This is the second half of my article about thought experiments and using your imagination in the study of prehistory. But this idea could be applied to any number of tasks. Please read the first article by clicking on this link

or scroll down to see it below this one.

In the first article, I detailed thought experiments by Galileo and Einstein along with my own imaginings plus a current example. But the main point of the article is to encourage others to use their own imaginings in their work.

So the following is an example of how you could use your imagination. But, of course, there are many ways to do this.

INTRODUCTION

Take A Trip To Ancient Mesopotamia

An imaginary walkthrough a Sumerian City thousands of years ago

This time period and culture of Mesopotamia is perhaps easier to imagine than an earlier time since it is a civilization much like ours. It is the first civilization that, in many ways, created or invented or designed a way to organize a society in a manner that continues to this day.

I have used a variety of images to create a feeling of "you are there." There are many contemporary or recent images, for example, that are appropriate for Mesopotamia 5000 years ago, such as the various round coracle boats. Every element I describe was present in Mesopotamia, but this city I describe is a conglomeration of different early Sumerian cities. My idea was to kickstart your imagination, to give you a description where you could see an ancient city with your own eyes as a functioning metropolis.

I took considerable liberties with the pictures I used. I was often not able to find ones that fit the exact time period but could find ones that fit the general time period. So I figured it was better to have something to illustrate what I was trying to show rather than nothing. Since this is fiction, I felt I could do this.

If you want to go on your own journey (which I hope you might), study the time period or the aspects you are interested in before you put yourself back in time. Try to be specific with your details and have enough details to paint a full picture.

***PLEASE NOTE, This is a fictional composite of a typical Mesopotamian city at this time but based on my ideas and research -- another person might paint a different picture. In any case, you will be taken away from your modern point of view and be looking at the world very differently, a world from 5000 years ago. You will be unlearning the present and looking at the past from its POV.

THE STORY BEGINS

***CLICK ON ANY PICTURE TO

START A SLIDE SHOW

OF THE IMAGERY IN THIS BLOG***

TIME-TRAVEL TO A MESOPOTAMIAN CITY 5,000 YEARS AGO

Imagine for a moment that you are studying ancient civilizations. For the last several nights you have been reading about Mesopotamian myths and kings and how the first civilization came to be.

Cylinder Seal Clay Impression:

Adda Seal Akkadian Empire 2300 BCE.

The images in this impression from a cylinder seal are of Mesopotamian gods and goddesses.

Each seal was unique and similar to the embossed stamp of a notary today. The stamp was used to mark personal property and to make documents legally binding. The seals were made with a "negative" cylinder (below) which when rolled on soft clay produced a positive as can be seen here.

Like many histories, what you found focuses on kings and empires, and palaces. While these are fascinating and quite unusual, you wonder what life was like for an average city dweller who lived in the world's first cities.

Late one night you sit in bed and continue reading about Sumer also known as Mesopotamia. You become increasingly interested until, quite suddenly, you are transported in space and time to a Sumerian city thousands of years ago, long before Rome and Egypt. It's like taking a plane to another world.

When the movement stops you find yourself next to the city's wall on a flat roof of a tall building overlooking the city.

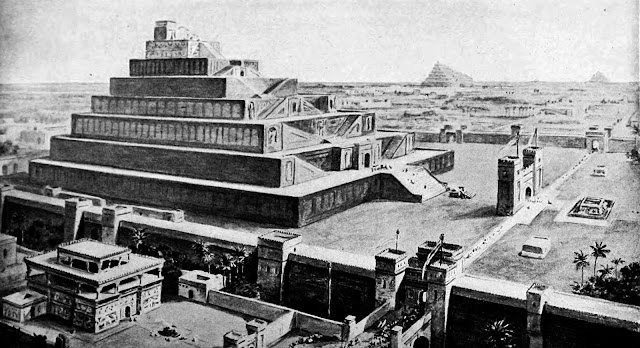

The ziggurat of this city with a view of two other ziggurat towers across the plains. In the flat land of Mesopotamia, the high ziggurats could be seen for kilometers. A ziggurat could be as tall as 30 meters or about 100 feet high.

Babylon and its Three Towers (original picture by William Simpson, 1904).

In front of you is the city's ziggurat temple that rises high above you. In the distance, many kilometers away over the plains, you can see two other cities with the peaks of their ziggurats reaching to the sky. They are magnificent and they take your breath away. Between these cities are thousands of acres of fields that supply the food for the urban dwellers.

A drawing of the ziggurat and palace complex. The palace was always close to the ziggurat.

"Reconstructed Model of Palace of Sargon."

From your reading, you know that the ziggurats are always close to the center of a Mesopotamia city and built high to bring them nearer to the gods who live in the heavens. And the royal palace is close by.

A clear picture of a ziggurat's design.

LEFT: A sculpture of the God Ea.

MIDDLE: The priest-king whose power came from the city's patron god who passed his authority down to the king.

RIGHT: A priest. The priests were the administrators and bureaucrats who ran the city.

The temple is also where the patron god of the city dwells. But while the building dominates the cityscape and the people below, ordinary people are never permitted in them, only priests and royalty are allowed.

Now, catching your breath, you realize you are dressed in modern clothes and you will stand out and be noticed. You climb down a steep set of stairs only to find a large pile of trash on the street. Someone has thrown away a perfectly good linen tunic and some sandals which happen to fit you just fine. After changing quickly into these clothes, you now feel it's okay to wander and see how this city is put together.

A street in Morocco probably similar to streets in Mesopotamia.

The city is composed of narrow winding streets which are confusing at first, yet you find you can always orient yourself by looking at the ziggurat. But the heat is oppressive.

A large reed ship -- an artist's conception but probably a fairly accurate depiction.

Click to see the source of this picture.

Click to see the source of this picture.

You walk toward the river and from a high vantage point you see several large ships made of reeds unloading their cargo. One ship is delivering hundreds of reed bundles and leather goods.

A model of another large reed ship, the Tigris. This could carry 50 tons of cargo. Thor Heyerdahl built the full scale ship to prove the sea worthiness of reed ships. He sailed the Tigris with no problems for 5 months in the Persian Gulf.

"Model of the reed boat Tigris, boat of Thor Heyerdahl." https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tigris_Model_Pyramids_of_Guimar.jpg

Another ship has come from the Persian Gulf, more than a thousand kilometers away, bringing wood and copper ore and tin ore for smelting bronze. Although these cities invented bronze, the ore had to be imported.

Coracles or round basket boats.

LEFT: This is a coracle which is also called a basket boat because its structure was/is created with reeds like a basket. In this picture, one can see the basket-like structure inside the boat. These boats have been used for thousands of years.

RIGHT: Quffa (coracle) in Baghdad in 1914.

"A kuphar (also transliterated kufa, kuffah, quffa, quffah) is a type of coracle or round boat traditionally used on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in ancient and modern Mesopotamia."

Next to the large ships are small round coracles known as basket boats because they are built with reeds like a basket. They are used locally to deliver goods on the river. They can be quite small or quite large.

A variety of smaller reed boats made up the Mesopotamian fleet.

(TOP) Mesopotamian small reed boats in a battle circa 700 BCE.

A drawing made from the relief of the battle (bottom).

A drawing made from the relief of the battle (bottom).

Picture from A History of Babylon.

(King, Leonard. A History of Babylon. London, Chatto and Windus, 1915, p. 201.)

BOTTOM

The original of the above drawing.

A relief depicting a military campaign circa 700 BCE, showed that smaller reed boats were widely used and had been used for thousands of years up to that time.

From the South-West Palace at Ninevah, Iraq. British Museum.

And various small reed boats are also available.

You start to feel a bit more comfortable because since it is a port town, you realize that locals might assume you are a sailor from another city and not be bothered by your different look.

Cuneiform Accounting. -- writing was invented to keep track of supplies and transactions.

Cuneiform tablets were made with a sharply cut reed stylus that made marks on soft clay -- the world's first writing. The well-educated scribes who knew how to write were held in high regard.

"Economic text from Shuruppak (Tell Fara), Iraq. Six columns of a cuneiform text mentioning various quantities of barely, flour, bread, and beer."

Early Dynastic period, c. 2500 BCE. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul, Turkey..

You notice that down at the docks, a man dressed in special clothes appears to be recording the cargo as it comes off a large boat. He takes a short reed stem that has been cut to a sharp angle and inscribes symbols onto a small piece of soft clay. Writing has only just been invented and is still being developed.

Main street view of the city.

You then walk the main street wondering what you will find next. The streets are made of fired mudbricks that are set in place with bitumen, a material similar to asphalt. The wheel has just been invented and it is still being developed. So you see materials being hauled on sleds pulled by donkeys along with the occasional cart with early wheels also pulled by a donkey.

You notice large piles of trash on just about every street corner. Some have a pungent odor. Apparently, trash is allowed to accumulate for months before the citizens and city take it all out to a dump site far away.

Just about everywhere you go you notice small shrines. You remember from your reading that there are over 3,000 gods although there are a much smaller number of principal gods worshiped in the ziggurat. And there is only one important patron god or goddess for each city.

Parts of Inanna temple facade -- a recreation.

"In a temple precinct dedicated to a goddess Inanna, a new temple was erected in the late 15th century BCE in Uruk."

Suddenly you find yourself next to the temple complex, the area where most of the temples are located. And you come upon the impressive façade of the Inanna Temple. Inanna translates as the "Lady of Heaven" and she was greatly revered. She is the goddess of love making and procreation. In addition, male and female deities are part of the facade. They are holding jugs of water, a symbol of fertility.

The Warka Vase

LEFT: Full photo of the vase

RIGHT: Detailed photo of each level.

"Warka vase, a slim alabaster vessel carved [with these images]...from bottom to top with: water, date palms, barley, and wheat, alternating rams and ewes, and men carrying baskets of foodstuffs to the goddess Inanna accepting the offerings."

The votive Vase of Warka, from Warka (ancient Uruk), Iraq. Jemdet Nasr period, 3000-2900 BCE. The Iraq Museum, Baghdad.

And perhaps by accident, a tall ritual vase is standing next to the facade -- maybe they were cleaning inside and knew that no one would dare tempt the anger of the gods by touching the vase. The vase offers a complete view of the Sumerian view of the world. On the bottom are water and plants, next up are animals, then people, and finally the gods that the people can relate to by giving offerings. From your studies you know it is the first time a culture has placed humans in a position in the divine order. It is almost too much to absorb.

A royal orchestra.

"Elamite Royal Orchestra (detail,British_Museum)" Relief.

And you also hear a complex sound coming from the palace. It sounds like an orchestra but you find it hard to believe that the Sumerians had such a thing, yet they did.

A coppersmith selling and making new items from copper.

Copper was available from the beginning, but bronze did not develop until much later and was difficult to make, expensive and used mainly for weapons and cart hardware.

Next, you find yourself in a commercial and work district. You can see into the open doors of shops and workplaces. There are basket shops where baskets are made and sold, along with leather working businesses, jewelry-making, gold smithing, breweries, bakeries, cart makers, and metallurgy.

A shop displaying baskets and "products weaved from plant fibers, Marrakesh."

A donkey with traditional panniers (side-saddle-type baskets). Heavy-duty reed baskets were used to dredge the channels, carry clay to make bricks, and carry bricks to build buildings.

In the markets and on donkeys, baskets made of reeds seem to be everywhere. Women carry baskets, stores display their goods in baskets, and donkeys carry bricks and other items in heavy-duty work baskets. While you had learned in your studies during the 21st century that this was the beginning of the bronze age, there is very little bronze to be seen. Plows in the outlying fields are still made of stone attached to wood.

LEFT: A potter at work on a potter's wheel.

The potter's wheel was an invention by Sumerians, invented before the wheel was used on carts.

The wheel led to the mass production of pottery. But it also allowed the potter to easily and quickly make a smooth even symmetrical shape.

RIGHT: "Pottery from the Late Uruk period: wheel-made pottery,"

Vorderasiatisches Museum (Near East Museum), Berlin.

At another shop, you are fascinated. You see pottery being mass-produced on a potter's wheel, a device that the Sumerians invented even before the wheel for carts. You see a lump of clay come alive in just a few minutes, as the wheel turns and hands shape the material to make a bowl or a cup or a vase, or a pitcher. These Sumerians, you now realize, are masters of clay since they have so much of it.

From your reading, you know that Mesopotamia lacked many recourses such as stone and quality wood. So they did the best with what they had such as clay.

A market.

Market in Boumalne du Dades, Morocco, Africa.

Building a temple with the best quality fired bricks.

Everything seems to orbit the ziggurat at the center of the city. And there the buildings are magnificent. They are all made of the finest high-quality fired-brick, such as the temples and palaces for the royalty, the priests, and the rich. But as you walk further away from the center the buildings become less and less opulent.

A model of family home made with bricks.

"Terracotta model of a house from Babylon, 2600 BCE, Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum, San Jose, California."

Away from the center, people who are well off but not rich live in homes made of sun-baked mudbrick. This brick is not nearly as strong as the fired brick and some homes are in disrepair and some have even collapsed.

Iraq's Marsh Arabs used reeds to build vaulted reception halls called mudhifs. Mudhifs were large ceremonial buildings and meeting places. Families lived in similar but much smaller reed hones, called rabas. All indications are that these buildings were made in the Neolithic period and continued to be built in the poorer areas of the cities and in rural areas for thousands of years up to today.

At another high point, you can see beyond the city walls where there are traditional grass huts, made from the abundant reeds that grow wild in the huge marshes.

Rivers, channels, and marshes were key elements for a Mesopotamian city. They were the highways before roads were built.

LEFT: A view of the river next to the city.

RIGHT: The river bank with coracles. River traffic and transportation were crucial to these cities.

And you can see that on the river and channels are hundreds of reed and coracle boats of different sizes and shapes. They are like taxis and the river and channels are more important than roads in the early days of Mesopotamia.

As said in the Sumerian epic Gilgamesh, the oldest story and myth written down, the Sumerians are quite pleased with their first cities that they made out of almost nothing, such as clay and reeds. They are proud of their walls, streets, markets, temples, and gardens.

A garden on the Euphrates river.

You find that you cannot go more than several blocks before you come upon another garden. The gardens are full of a variety of plants and are well-kept.

Traditional Middle East sundial.

"Sundial with Aramean Inscription, Sandstone...found in Madain Saleh."

Istanbul Archaeological Museums - Museum of the Ancient Orient, Inv. No. 7664.

Every garden seems to have a sundial.

There is something very soothing about them in the middle of the noise of a bustling city where you can hear the donkeys braying, the clank of metal at the metal smiths, carts and sleds going down the roads, and always a song or two or the chords of a musical instrument that drifts out from a doorway. And musicians are often playing in the gardens as well.

A detail from the Standard of Ur. On the left is a man drinking beer, in the middle a man playing the lyre, on the right, a woman singing.

Now tired from your sudden change and the new culture, you go to one of many beer parlors. Your luck seems to be holding because in your wanderings someone had dropped a couple of coins, known as shekels, that you found. You hand one to the tavern owner, and she gives you a huge beer in a pottery cup. The beer is so rich it is almost like a meal. It is made from the main crop, barley. The goddess, Ninkasi, is the Mesopotamian goddess of beer and brewing and Sumerians praise her in a hymn that also details a recipe for making beer.

"Plaque with musician playing a lute, Ischali, Isin-Larsa period, 2000-1600 BC, baked clay."

Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago

When you sit down, the musicians, who were taking a break, come back and begin to play. It is a duo. A man plays the lyre while the woman sings and the tuning is very strange. You think, "It's almost like the 21st Century." Because of the loud response by the crowd in this beer joint, who sing along and know all the words, you think it must be the hymn to Ninkasi that you read in translation just before your journey.

NinkasiIt is you who soak the malt in a jar; the waves rise, the waves fall.It is you who spread the cooked mash on large reed mats; coolness overcomesIt is you who hold with both hands the great sweetwort, brewing it with honey and wine

Tired but not knowing how long you will be able to explore your new world, you finish your beer, which has gone a bit to your head, and move on. Now that the sun is starting to set, the crisp angles of the brick buildings create sharp shadows that lengthen down the streets.

You find yourself at the bottom of the steps where you first arrived and you walk up the steps to gain an overview as the sun fades. You see families across the wealthy residential areas sitting on their flat roofs to have an evening meal and sing songs and tell stories. Dim lamps on these roofs are scattered throughout the growing darkness.

And when the sun does fully set you are surprised at how dark a city of this size becomes. Now down at street level, the light of a few sesame oil lamps appears from doorways. But although there is no moonlight, the sky is clear and your sight adjusts to the darkness. You are surprised that you can see your way with just the light of the stars.

The stairway to the Ziggurat of Ur.

And you know from your reading, that the priests in the ziggurat are probably making astronomical observations on a clear night like this. The nighttime is a time for this magnificent building to be a "highway to heaven."

The reconstructed city walls of Babylon.

The entrance to the outside of the walls.

You walk toward the edge of town, go through an archway and realize that you are now outside the walls and also in an area that is almost like another city unto itself. Thousands of small homes made out of reeds and reed mats stretch to the river. This is where most farmers and many other commoners live.

"An Arab Village of Reed Mats...on Lower Euphrates, Mesopotamia."

While the city inside the walls has clear, if narrow winding streets, this part of the city is more of a hodge-podge. Houses clump together in odd configurations and strange angles and the path through them is not obvious. There is often an unpleasant smell of human waste.

A pile of mats. Mats were an all-purpose item,

They could be used on floors, as walls, and as a roof. [2]

They could be used on floors, as walls, and as a roof. [2]

Suddenly you become aware that you are hungry and have nowhere to sleep. But as you go through these homes of common people, a couple notices you are a stranger and probably lost and invites you into their raba or "grass hut" as they are called, A raba is a small version of the very large well made ceremonial reed buildings called mudhifs, buildings which have been constructed for thousands of years before the cities appeared. Rabas can be large enough for a family and quite comfortable. They are made entirely from reeds, even the rope.

Mudhif under construction with light coming through the reed lattices.

As you look around you see that the whole neighborhood, as far as you can see, is composed of these huts. You have left the world of brick. As you follow your new friends to their home, you can see light from fires that spills out of doorways and the lattice work at the front.

Inside the hut, it's almost like being in a large tent. The dirt floor is covered with reed mats, and on the edges are chests and hampers made of reeds. There is a fire in a dirt pit lined with hardened clay.

You sit at a table with the family and their eight children to enjoy a stew of beans, beets, and cabbage flavored with unusual spices and onions along with fish from the river and barley bread, and, of course, beer.

The faithful.

LET: "Standing male worshiper ca. 2900–2600 BCE. Sumerian"

RIGHT: "Statuette of a standing Sumerian female worshiper. Early Dynastic Period, 2600-2370 BCE."

From Diyala Region/Valley, Mesopotamia, Iraq. On display at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad.

Before eating you clasp your hands together as your guests do and the evening prayer is said. In the corner of the house is a small shrine that is private and used only by the family.

Because you are a guest, they serve you a special cake sweetened with honey. As you eat your dessert one of the children tells a story and everyone laughs. Then another child tells her story and then a parent tells a story. After that music begins. Everyone either plays an instrument or sings. The boy bangs a drum and a girl plays a string instrument that looks like a lute or mandolin. You now realize music is an important part of Sumerian life almost as much as the daily religious rituals.

Sitting on the comfortable reed mats, you lean back a bit and enjoy the moment.

"The head of a Goddess of Uruk on white marble circa 3000 BCE."

But suddenly you wake up and realize you are in your own bed and the sun is rising. It's the 21st Century.

Was it a dream? No matter, it felt real. And what could you learn from your visit? What could the first civilization tell you that might benefit the modern world or help us have a better understanding of the past?

You are left with the lingering image of a woman -- that must have been in a garden although you don't remember where. Her picture stays with you all the next day as she seems to sum up your feelings about your journey.

[1] brown_u_landscape.pdf

[2] brown_u_landscape.pdf

_1A.jpg)

aA.jpg)

A.jpg)

AA.jpg)

_DRAWING.jpg)