The Importance of Processes

in the Paleolithic Era

Free Download

A PDF of this blog-article at:

https://unc.academia.edu/RickDoble/DRAFTS#drafts

ALSO FREE:

The Illustrated Theory

of Paleo Basket-Weaving Technology

by Rick Doble

Download a 200-Page PDF eBook

-- no ads/no strings --

DOWNLOAD NOW

Figshare

Academia.edu

PROCESS DIAGRAM: PROJECT TINKERTOY (Early 1950s)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Project_Tinkertoy

Project Tinkertoy facility - "Code-named Project Tinkertoy, the major objective of the program was the design and construction of a pilot plant compatible with the principles of modular design and mechanized production of electronics... NBS intended to develop a process for automated manufacture of electronic equipment and to demonstrate it on a pilot production line."

National Institute of Standards and Technology

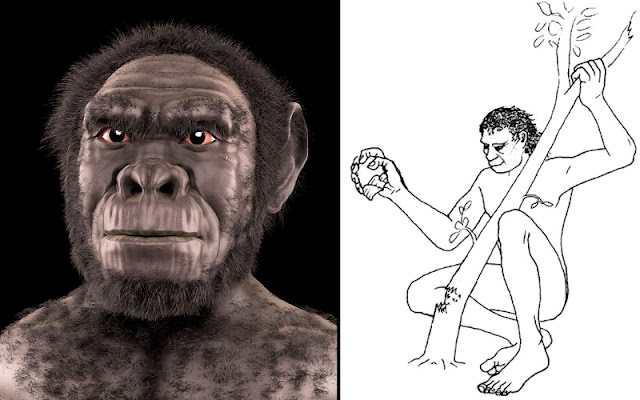

"Recent studies have shown, however, that even among the oldest sites flakes do indicate high levels of skill. For example, at Gona, Ethiopia, material dated to 2.5-2.6 myr represented skillfully flaked lava cobbles (Schick and Toth, 2006; Semaw, 2000)...Evidence suggests that skillful flaking and forethought were components of human tool production even as early as 2.5 million years ago..."

Turcotte, Cassandra M. "Oldowan Stone Tools." The Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology (CASHP). http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/origins/oldowan_stone_tools.php

To begin the stones that were often used were river pebbles. Choosing the right stones was crucial and it appears that Homo habilis became quite skilled at this.

Hammerstone: This was the stone that was used to strike the core and break off a flake. This stone was round, fat, hard and could be easily held in the hand. It also would not shatter.

Core: The core was the stone that was struck. The core was generally a crystalline stone such as quartz, basalt, flint or chert. Obsidian was particularly desired as it made the sharpest edge. Naturally, it depended on what was available. The abundance of these kinds of rocks that were used for these tools shows that Homo habilis knew the difference between rocks. They understood which stones were best for holding a cutting edge.

Striking the Core: The core had to be hit at just the right angle, at a certain point and with the correct amount of force. Hitting the core could produce sharp flakes that became tools in themselves or the core could be hit in such a way that when a flake was removed, the core was left with sharp cutting points. This was then called a chopper and may have been used to cut plants or chop a tree or butcher an animal.

Flake: The flake was the fragment that split off from the core. Producing a flake with a sharp edge was often the reason for hitting the core. A flake was then a tool in itself which could be quite sharp, as sharp as a surgical knife today, depending on the core's material.

Handling these tools: The blunt side was called the proximal surface and the sharp surface was called the distal surface. The proximal surface was held in the hand and then the sharp distal surface was used to cut.

Conchoidal fracture: The fracture this process produced is known as a 'conchoidal fracture' which does not happen in nature and can only be produced by a deliberate sharp impact. This kind of fracture makes a solid tool that keeps its integrity and is not prone to breaking apart. And because this does not occur in nature, it is clear that these tools were man-made.

The general name for this kind of technology is percussion technology.

"The Oldowan represents the first instances of technological innovation in human history, wherein our ancestors first began to enhance their biological abilities with the manufacture of stone tools...Tool production and use is thought to be intimately linked to, if not the instigator of, major changes in cognitive development..."EARLY STONE-TOOL PROCESS EVOLUTION

Turcotte, Cassandra M. "Oldowan Stone Tools." The Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology (CASHP). http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/origins/oldowan_stone_tools.php

The initial Homo habilis stone-tool process:

The Oldowan Technology

"These early tools were most likely used to help these humans butcher animals...cut up plants, and even do some woodworking...Stone is simply pretty good at standing the test of time, but it would not have been the only thing these people used in their daily lives. It is likely that a whole range of material spanning from skin and bark [were] used to create containers; wood used to create digging sticks, spears or clubs; and digging tools made out of horn or bone were also used."

The next and more complex Homo erectus process:

The Acheulean Technology

"While the Oldowan was still in full swing...Africa became the initial host to a second tool industry: the Acheulean (c. 1,7 million years ago to c. 250,000 years ago)...It saw the development of tools into new shapes: large bifaces like hand axes, picks, cleavers and knives enabled the contemporary Homo erectus...to literally get a better grip on the processing of their kills and gatherings. More precisely shaped tools meant a more delicate technique was needed; and indeed, softer materials such as wood, bone, antler, ivory, or soft stones, were now used as percussors in what is known as the soft hammer technique."

Groeneveld, Emma. "Stone Age Tools." Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited, 21 December 2016. https://www.ancient.eu/article/998/stone-age-tools/It is important to note that In the Acheulean stage, stone-tool making had now developed so that hominins were making tools to make the tools, known as meta-tools -- a critical meta-step in the technology. So this process was not only more complicated but it included another level of cognition and planning.

"In whichever way archaeological remains are interpreted, one must always be aware that the vast majority of the materials with which prehistoric people were surrounded and with which they worked is lost to us today. ...organic materials start to decay as soon as they are deposited in the ground."

Grömer, Dr. Karina. "An Introduction to Prehistoric Textiles" Brewminate.com, Natural History Museum, Vienna, March 01, 2016, https://brewminate.com/an-introduction-to-prehistoric-textiles.

Dr. Adovasio has made the point that there is "ample ethnographic evidence that perishable technologies form the bulk of hunter-gatherer material culture even in arctic and sub-arctic environments (e.g. Damas 1984; Helm 1981). Archaeologists working with materials recovered from environmental contexts with ideal preservation clearly confirm that this is also true for the past as well. Taylor (1966:73), for example, notes that in dry caves he recovered 20 times more fiber artifacts than those made of stone, Croes (1997:536) reports that wet sites yield inventories where >95% of prehistoric material culture is made of wood and fiber, and Collins (1937) confirms the same for sites in Alaskan permafrost."

Soffer O, Adovasio JM, Hyland DC, Klíma B, Svoboda J. "Perishable Industries from Dolní Vestonice I: New Insights into the Nature and Origin of the Gravettian." Paper Prepared for the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology Seattle, Washington, 25–29 March 1998. DolniVestonice.pdf.

According to The Evolution of Culture, very few animals possess the ability to learn via imitation. But the genus Homo was/is one of them. (The Evolution of Culture, Volume 4. Linquist, Stefan, Editor. Rutledge, 2017.)"The first obvious signs of imitation are the stone tools made by Homo habilis about 2.5 million years ago, although their form did not change very much for another million years. It seems likely that less durable tools were made before then, possibly carrying baskets, slings, wooden tools and so on."

Blackmore, Susan. "Evolution and Memes: The human brain as a selective imitation device." Cybernetics and Systems, Vol 32:1, 225-255, 2001,Taylor and Francis, Philadelphia, PA.

"Stone toolmaking action analyses...demonstrate the presence of cumulative cultural evolution in the Lower Palaeolithic and suggest that this accumulation displays an accelerating rate of change continuous with that seen in later human history. This should encourage interest in intrinsic processes of cultural evolution that might tend to produce such a uniform curve, including the potentially autocatalytic effects of increasing technological complexity...Lower Palaeolithic technologies clearly do increase in hierarchical complexity through time, raising the possibility of important interactions with the evolution of human cognitive control..."

Stout, Dietrich. "Stone toolmaking and the evolution of human culture and cognition." Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011 Apr 12; 366(1567):

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3049103/

"Increasing levels of abstraction in action organization place demands on increasingly anterior portions of frontal cortex [22] and precisely this pattern of increased anterior activation has been observed in a brain imaging study comparing late Acheulean versus Oldowan toolmaking [29].This is consistent with the possibility that evolving neural substrates for complex action organization could have interacted with autocatalytic increases in technological complexity to produce a ‘runaway’ process of biocultural evolution [8,65]."

Stout, Dietrich. "Stone toolmaking and the evolution of human culture and cognition." Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011 Apr 12; 366(1567).https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3049103/

"Our sense of time involves some sense of duration and also of the differences between past, present and future. There is evidence that our sense of these distinctions is one of the most important mental faculties distinguishing man from all other living creatures. For we have good reason to believe that all animals except man live in a continual present."

"It must have required enormous effort for man to overcome his natural tendency to live like the animals in a continual present."

Whitrow, Gerald James. Time in History: Views of Time from Prehistory to the Present Day. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press. 1988, pages 7 & 22.

In the late Paleolithic period, tools became even more sophisticated. As many as 80 different types of implements have been unearthed for what are called the Perigordian and Aurignacian industries in Europe. It is believed that these tools were used for hunting and butchering, clothes making, and a great variety of other tasks that moved early humankind closer to modern life. In all, hundreds of highly complex tools have been found, some of which are the prototypes for modern tools.

STONE TOOL INDUSTRY

https://www.britannica.com/topic/stone-tool-industry

The "silcrete heat treatment...may provide the first direct evidence of the intentional and extensive use of fire applied to a whole lithic chain of production."

"This heating process marks the emergence of fire engineering as a response to a variety of needs that largely transcend hominin basic subsistence requirements,"

"Early humans used innovative heating techniques to make stone blades." Science Daily. October 20, 2016.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/10/161020092107.htm

"This part of the association cortex, which is implicated in higher cognition and affect, is thus disproportionately large in humans relative to other primates."

Stern, Peter. The human prefrontal cortex is special. Science. Science22 Jun 2018 : 1311-1312.

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/360/6395/1311.7

"This brain region has been implicated in planning complex cognitive behavior, ... [and] decision making...The basic activity of this brain region is considered to be orchestration of thoughts and actions in accordance with internal goals." [ED: i.e., the future]

Prefrontal Cortex. The Science Of Psychotherapy. 2017.

https://www.thescienceofpsychotherapy.com/prefrontal-cortex/

"Tools are the products of our brains, and we have millions of stone tools," Wynn added. "What we need are more creative ideas on how to extract understanding from them, and what they tell us about our evolution." Quotation from paleoanthropologist Thomas Wynn of the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

Choi, Charles. "Human Evolution: The Origin of Tool Use." LiveScience, November 11, 2009. https://www.livescience.com/7968-human-evolution-origin-tool.html. Accessed 10/26/2019.